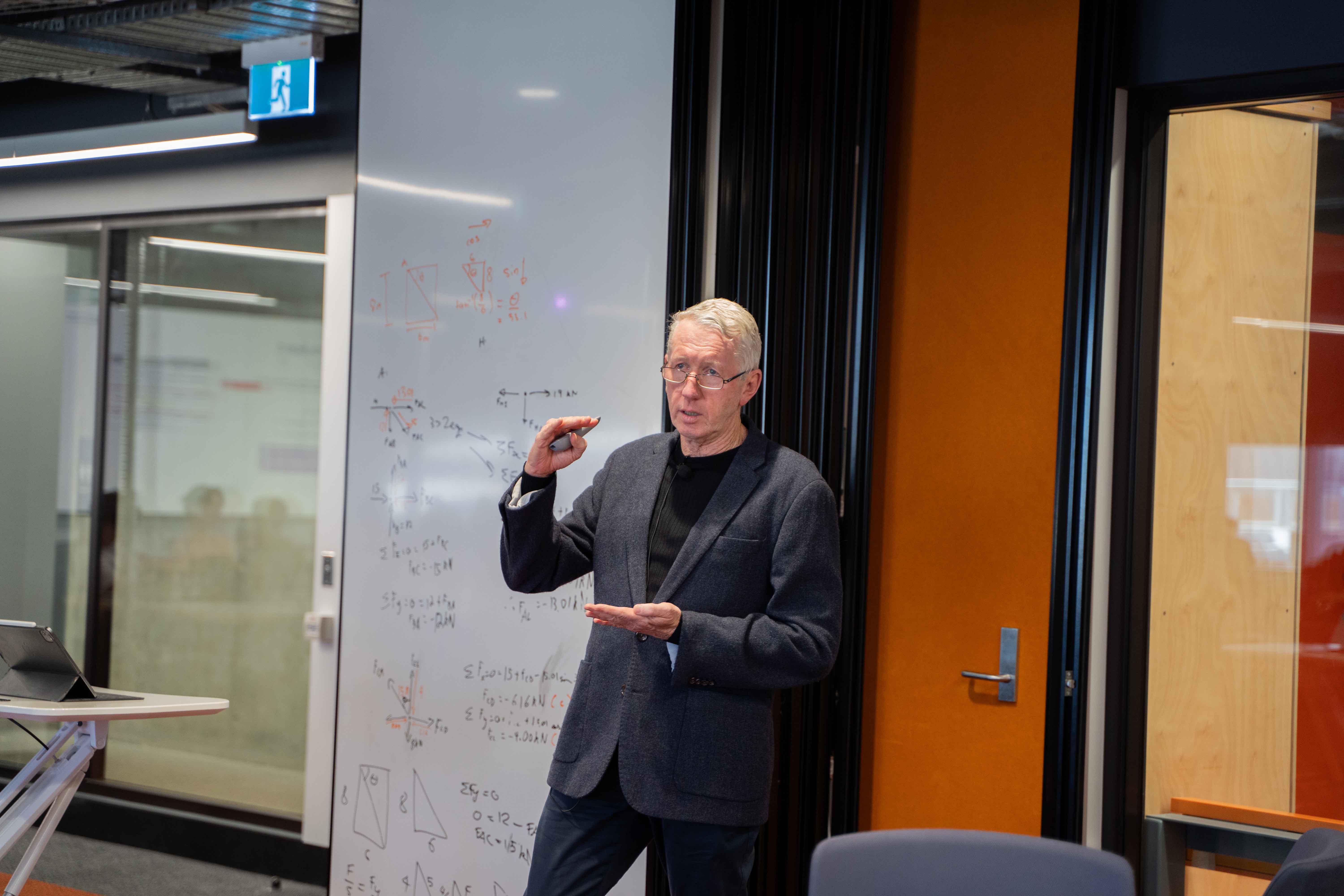

For the first twenty years of Peter Dawson’s career, the most advanced equipment in his architecture office was a fax machine. A lot has changed since he sent his first email in the late nineties, and Mr Dawson admits his contemporary students are more adept at using new technologies than he ever will be.

But it is precisely these decades of experience in professional practice that supports practitioner–educators such as Mr Dawson to enhance the quality and relevance of architectural education. In sharing their first-hand industry knowledge and connections, they are helping to shape students into innovative problem solvers equipped to meet the complex challenges of our changing world – including the evolution of technology.

“I have been a keen adopter of tools that increase the quality and efficiency of my work, but I’ve bypassed those that add needless complexity and expectations,” Mr Dawson says.

“Students are more proficient at the application of new technology, but my experience allows me to guide their selection of the right tool for a given task and avoid the techno-trap of doing things ‘just because you can.’”

Mr Dawson is an Industry Fellow and co-ordinator for professional practice courses in the UQ School of Architecture, Design and Planning (ADP). He also maintains his role as a consultant at Architectus Conrad Gargett, where he was formerly a principal.

He says he was led to pursue a career in architecture by “an inner force” and was immersed in the field from as early as he can remember, with his father running a small firm in Brisbane. After completing an architecture degree he travelled and worked overseas, and then returned to Brisbane to work in practice and teach when the opportunity arose.

“I see the profession as a seamless entity containing education, practice and research,” Mr Dawson says.

“Sharing knowledge and experience, particularly from one generation to another, is essential to this ecosystem. I counsel students to seek out friendships with older and younger people in their lives for the wisdom and enthusiasm they bring to the present moment.”

Teachers who are active in professional practice are integral to the School of ADP, and this extends from teaching staff like Mr Dawson, Kim Baber (Baber Studio) and Dr Ashley Paine (PHAB Architects), to guests and sessional teachers. For Semester 1 2025, renowned architects Stuart Vokes and Aaron Peters of Vokes and Peters have joined the School to teach Architectural Practice: Design (ARCH7043); and Jim Gall of Gall Architects is teaching Climate Futures and the Built Environment (ARCH7033).

Semester programs also include lectures and panel discussions featuring renowned architects, specialist engineers, managers and building contractors, which provide a wonderful opportunity for students to learn from professionals they may encounter at work in the coming years.

While both architecture academics and industry professionals have in-depth knowledge of the field, educators who actively bridge this theory–practice divide can share unique real-world experiences from their work, along with dynamic industry knowledge, professional networks, and valuable mentorship on navigating the professional landscape.

Mr Dawson says one of the most important lessons relates to organisation and time management – something he says architects have traditionally struggled with.

“It brings up issues of working hours, creativity and commercial pressures. I have shared with the students some tools for organising and prioritising, but I also point out that for these to be effective, they need to be clear about their goals and values,” he says.

“It is important for students to curate their own careers. Career pathways might be structured to some degree in some larger practices, but ultimately it is up to individuals.”

For the practitioner–educators, there are rewards too. Design ideas and solutions developed by inventive student minds can act as a catalyst for more innovative thinking in the experts’ practice.

“My teaching role surrounds me with enthusiastic students in the final years of their studies. This lifts my spirits,” Mr Dawson says.

“My role also challenges me to distil forty-three years of experience in architectural practice into memorable lessons for them.”

Kim Baber, a Fellow in Civil Engineering and Architecture at UQ and Principal of Baber Studio, says being both an academic and a practising architect has enhanced his collaboration skills and informed his teaching methods. He says that in both practice and research, relationships are built on promoting respect between the disciplines and breaking down stereotypes, which is why collaboration is so important.

“The architect’s role in synthesising the ideas of the specialist disciplines is often more important to the project’s success than any one individual’s contribution,” Mr Baber says.

“In my role as an educator, I have brought a strong emphasis to teaching design through making by bringing interdisciplinary students together to collaborate on a built project ... they are asked to conceptualise a design, resolve the translation of ideas into a proposition, encounter and fix mistakes, document the way it is the be built, and then construct the final project together.

“The tacit knowledge gained through this process is both valuable and rewarding, and very difficult if not impossible to replicate virtually.”

Mr Baber says UQ’s Collaborative Workshop (CoLab) has played a significant part in this. The CoLab provides facilities and equipment for model-making and 1:1 scale prototyping. Students are encouraged to use the CoLab as an informal study area where they can test their designs with 3D forms and make “creative mistakes.”

In this setting, practitioner–educators also provide first-hand examples of their own built projects, which not only informs the students’ learning but can also serve as inspiration. After explaining the ideas and processes of the design, the educator might take students on a field trip to the site, to see the built outcome.

“In the CoLab, I try to recreate an experience for students that is closer to working in practice and on site, and it is extremely rewarding for them when they see a collaboration with others actually working, where they can conceptualise and realise their collective ideas together,” he says.

“All of a sudden, they get it, they see the potential for them being able to do it, too. Even though it takes a long time to get to that point after graduation, we need to remind them that it is worth pursuing.”

Dr Ashley Paine, Senior Lecturer in Architecture in the School of ADP and a founding partner of PHAB Architects, says using his industry experience to support students extends beyond teaching design skills in studios to also encompass history, theory and research courses.

“Developing a deep understanding of past architecture, and being critically engaged in contemporary discourse and practice, are vital skills for architects,” he says.

One of the most significant challenges in architectural education that Dr Paine has witnessed over time has been a lack of focus on wellbeing, with architecture degrees historically placing huge demands on students’ time and energy – something he saw throughout his own studies.

“I witnessed other students going without sleep for days on end, which, at the time, was seen not just as a necessity, but as a badge of honour,” he says.

“Thankfully, there is much greater awareness today of the need for a better, healthier balance of life and study, or life and work, and this is something I encourage for my students.”