Have you ever wondered how architecture influences the relationship between humans and birds, and the way we perceive our avian counterparts? School of Architecture, Design and Planning PhD candidate Natalie Lis has – and she’s spent the past five and a half years exploring it.

Her research examines a range of architect-designed and vernacular structures – such as chicken coops, industrial poultry sheds, cockfighting arenas, eider duck shelters, duck decoys, sky burial sites and penguinariums – to investigate how architecture shapes cultural and social symbolism and how birds are used as resources.

Principal advisor Dr Susan Holden said the research demonstrates impressive expertise in analysing how architecture mediates cross-species relationships, using methods from architectural history and human–animal studies.

“This is a relatively new and expanding area in the architectural humanities,” Dr Holden said.

“It is significant because it is helping the discipline of architecture to better understand its environmental and social impacts."

“Natalie’s research is already making an important contribution to this field, and to the challenge of how we can shape more ethical design practices.”

With a background in both linguistics and architecture, Lis brings an interdisciplinary lens to her work. Her professional experience in architectural practice in Queensland sparked her interest in how historical legacies can limit more-than-human approaches to architectural design, and she embarked on her PhD in late 2019. Her thesis is titled “How Architecture Changes What a Bird Means: Architectural Assemblies and Interspecies Relations.”

“By elevating and better understanding the status of nonhuman animals through serious scholarly enquiry, we elevate and better understand the status of all beings, including ourselves," Lis said.

“I do not separate humans from the animal kingdom in that ever-lingering Cartesian tradition. I look at the world, and our history, as an entwined global ecology. The intellectual separation that humans have used to place themselves on a different status to other animals has been destructive to our shared ecology at many levels.

“Many of the questions I answer through my research, for instance, expose the immense cruelties and exploitative systems that humans inflict on nonhumans, and each other, through the architecture that hosts large-scale industrial animal farming.”

Birds became a significant focus of her studies because she found them to be marginalised in ways that are unrecognisable in other human–animal relationships.

“They also have this fascinating ability to fly – and sometimes swim – incredible distances, shaping human lives in surprising ways,” she said.

While most current research frames bird loss as a modern problem linked to climate change and habitat destruction, Lis discovered that human impacts on avian species stretch back centuries.

“Current capitalist structures are unparalleled in history, making the situation dire for many avian species, but I was amazed to learn that duck driving [herding of wild ducks for large-scale slaughter] was banned in England by King Henry VIII because it was observed to be destroying water-fowl populations,” she said.

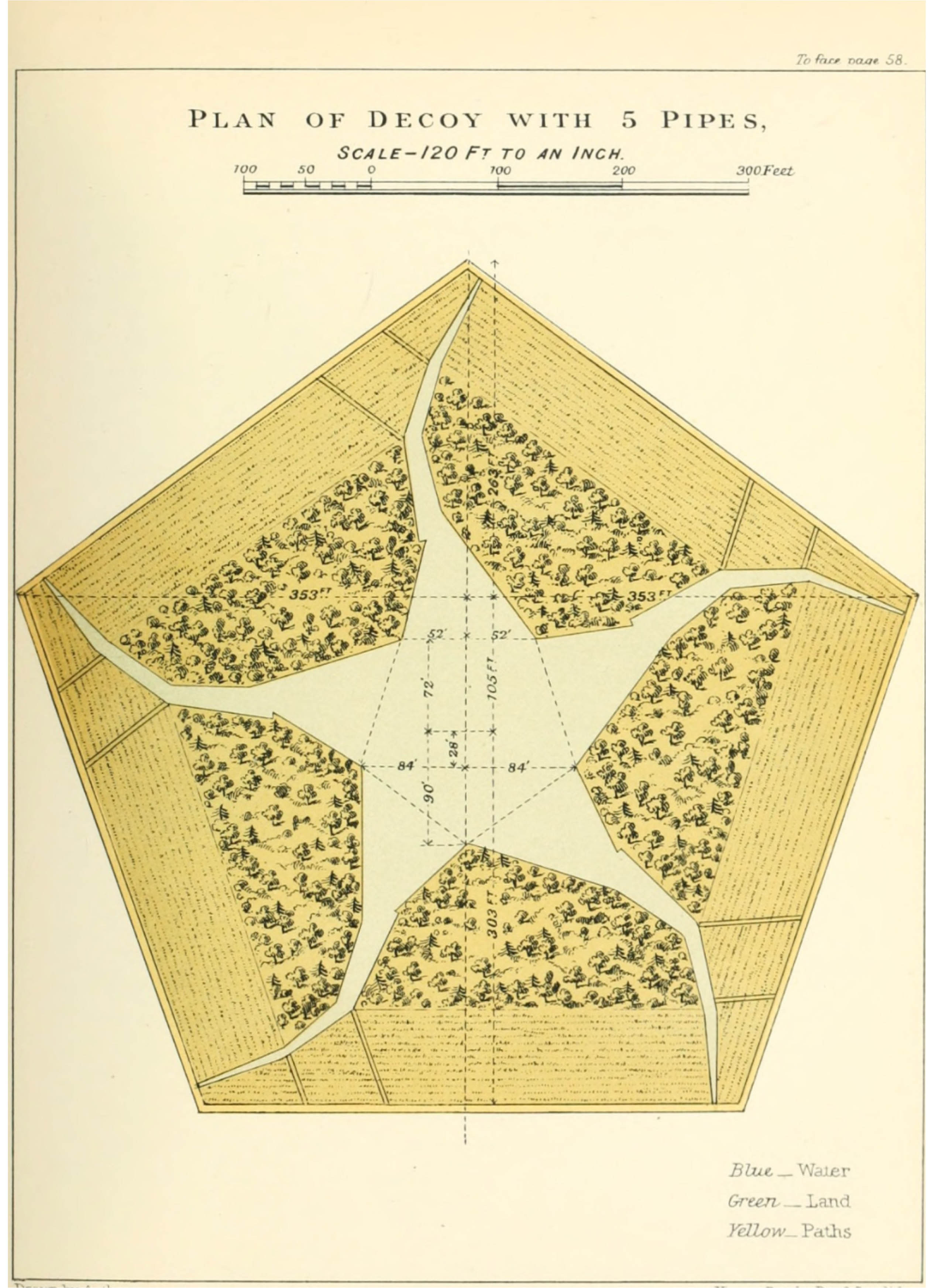

In the 17th century, duck decoys – multi-hectare open-top structures surrounding ponds – replaced duck driving and were used to collect large numbers of ducks for human consumption. These curious structures allowed birds to enter and exit freely, and were also sites where ducks could raise their young, protected from predators such as foxes and dogs.

Lis said that today, very few of these structures remain, and those that do are more closely linked to heritage and conservation despite their history, exemplifying changes in human cultural value and human relationships with wild ducks in such settings.

“Humans have long been entwined with birds in ways that are not always apparent on the surface."

Her research also examines material exchanges between birds and humans – where humans give a resource to a particular species and benefit in return. One example is the dakhma – a human-built avian architecture used in Parsi Zoroastrian death rituals. Here, humans provide the resource of a deceased human; vultures benefit by consuming the resource while also helping humans dispose of a corpse as part of the carefully orchestrated ritual.

“Digging into human–avian histories helped me understand not only the complexity of these interspecies relationships, but also how choices made by humans echo from history and shape our present moment. History plays a role in understanding the more-than-human world,” Lis said.

In addition to her PhD work, Lis is currently a course coordinator for Architectural Design: Form and Space (ARCH1100) at UQ and a committee member of the Australasian Animal Studies Association. She has presented numerous papers, including at conferences of the Society of Architectural Historians, the Australasian Animal Studies Association, and the European Society for Agricultural and Food Ethics, among others.

In 2020 she presented “Battle Birds” at the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, exploring how roosters are situated as avatars in cockfighting. Her recent peered-reviewed paper “Forest Birds on Pasture: Meddling Marketing and Conflicting Cultures” in Animal Studies Journal investigates chicken labour at poultry farms and provides a critical analysis of poultry husbandry structures.

After completing her PhD, Lis plans to research further human–avian relationships. Her goal is to combine research and teaching to explore how human–animal relationships across time shape life in urban, suburban and rural environments. She is working on a book and has academic publications in press.

“I have an overwhelming sense that the real work is about to begin,” she said.

“I learned so much from my advisors and my experiences in the PhD process, and I am ready to get to work on the next project.”

Lis acknowledges her partner, Eric Rising, her dog Gimli and “all the birds who I have ever known, don't yet know or will never know.”

Lis’s advisory team was Dr Susan Holden, Dr Ashley Paine and Emeritus Professor Sandra Kaji-O'Grady. Her PhD research has been supported by a 2024 Scott Opler Graduate Student Fellowship from the Society of Architectural Historians; a School Research Grant from the UQ School of Architecture, Design and Planning; and an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.